As a follow-up to my last post I was planning to talk a little more about the images I posted there. But before I get to that, I need to digest the latest wrinkle in this canon conflict--Franzen's Freedom has been named the latest Oprah's Book Club pick! (Of course I learned of this from a Barnes and Noble email.) This is a bit shocking because of the awkward kerfuffle that happened last time Oprah picked a Franzen novel, when the author said some disparaging things about the whole idea and got himself uninvited.

According to Reuters: "This time, Winfrey said she sent Franzen a note asking for his permission to feature his latest novel 'because we have a little history.'" I wonder if that means Franzen will appear on the show? If so, it's interesting to speculate what's changed in the literary world since 2001. My off-the-cuff guess would be that we're seeing a kind of flattening of the literary universe as professional critics thin their ranks and the publishing industry struggles to adapt to new realities. But on the other hand, it's entirely possible that Franzen won't go on the show, and that Oprah's taking the high road (as in both moral and -brow) on her own.

All of this circles back to the 'Franzenfreude' debate. The same things that presumably attracted Oprah to the book: its themes of American families, love and the struggle for a new domesticity (or so I hear, not having read it yet) are the same things that make the novel appealing to more than just the 'male readers' Franzen was so worried about losing during his previous Oprah spat. And of course these themes would (so critics argue) condemn Franzen to chick-lit middlebrow status if he happened to be a woman.

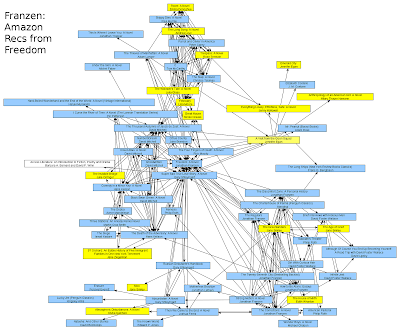

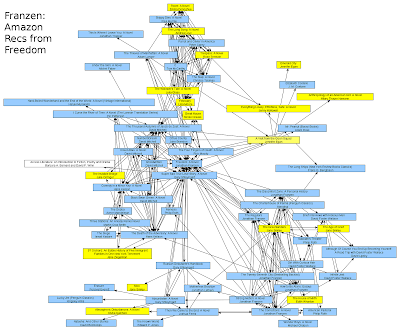

What we can glean from the images I posted previously is that Franzen really is successful at breaking out of the 'challenging young novelist' box. Unlike, say, David Foster Wallace (whom I'm working on right now), Franzen's books are avenues of exchange for readers of Jane Smiley, Jennifer Egan, David Mitchell, and a host of other writers of both sexes (though, it must be said, more men than women). Oprah's latest pick proves what we see in the images below: Franzen has managed to snag the ring of elite literary prestige while still appealing to diverse audiences. His books lead readers to varied literary clusters, not just to more Franzen. And his links to the canon-spanning roster of previous Oprah selections will only proliferate in the coming months.

Friday, September 17, 2010

Friday, September 3, 2010

Gender Bias in Reviews

I was fascinated to read an analysis Slate's DoubleX staff ran yesterday about gender bias in New York Times book reviews. They discovered that there is a significant slant towards men getting reviewed (and men doing the reviewing), particularly for authors who get the coveted double-coverage treatment (a review in the newspaper as well as one in the weekend Book Review).

One question they pose is about contextualizing writers—would Nick Hornby be a chick-lit writer if he was female? They say: “Our tools are not fine-tuned enough to answer these questions.”

As a former Slatester myself and a current grad student who's working in precisely this area (not on gender, per se, but on reviews, how writers become famous and how books live their own lives online), I have some tools I can bring to the table.

One of the reasons this stuff is hard to pin down is that the literary marketplace is vast, fluid, and poorly documented. The New York Times bestseller list is something of a black box itself, so why not take a look inside some other black boxes to see what distinguishes authors? This is the logic that has led me to spend some serious time looking at Amazon (after all, the world's largest bookseller) to see how authors get contextualized there. I decided to see what the gender breakdown is for books that are recommended1 from the main subjects of the Slate article: Franzen, Hornby, Weiner and Picoult (who kicked off the debate with an angry comment about Franzen's rave in the Times, if I recall correctly).

The results are shocking. See below: boys in blue, girls in yellow (click on the thumbnails to see larger images).2 Yes, Franzen and Hornby are linked to a lot more men than women—not too surprising. Weiner is linked almost exclusively to women—again, not a huge surprise. But take a look at Picoult—she is a literary island unto herself, according to the Amazon recommendation engines. This is very rare in my research, and I think indicates an author who's distinctive in a stylistically interior way—her books lead readers to more of her books, not to things outside the Picoult universe.

I did this quickly so I might have gotten a gender wrong somewhere or messed up a book network somehow, but as a quick sketch of the differences between Franzen, Hornby, Weiner and Picoult, I think this is quite interesting. (Or at least the perceived differences, which in the literary world are more or less the whole of reality anyway). I don't have a strong opinion in the debate; it seems clear that more men than women are reviewed in the Times, while it's almost certainly true that many more women than men read novels. But as some comments on the Slate article pointed out, gender bias doesn't happen in a vacuum--readers, authors and critics are all players in the same complicated literary game.

1. I look at these recommendations because I think they're one of our best models for what books people actually buy together. In practice books connected this way tend to jump the boring categories like genre and author and link together in much more idiosyncratic ways. Obviously Amazon plays with these results...but they're always trying to sell more books, and they're pretty good at it, so I use the recommendations as a best approximation of the marketplace.

2. "What am I looking at?" The nodes here are books on Amazon, and the arrows connecting them are recommendations from one book page to another. These results represent the first ten “Customers who bought X also bought Y" recommendations for each book, starting with each writer's most recent fiction publication (Freedom, Juliet, Naked, Fly Away Home and House Rules, respectively).

One question they pose is about contextualizing writers—would Nick Hornby be a chick-lit writer if he was female? They say: “Our tools are not fine-tuned enough to answer these questions.”

As a former Slatester myself and a current grad student who's working in precisely this area (not on gender, per se, but on reviews, how writers become famous and how books live their own lives online), I have some tools I can bring to the table.

One of the reasons this stuff is hard to pin down is that the literary marketplace is vast, fluid, and poorly documented. The New York Times bestseller list is something of a black box itself, so why not take a look inside some other black boxes to see what distinguishes authors? This is the logic that has led me to spend some serious time looking at Amazon (after all, the world's largest bookseller) to see how authors get contextualized there. I decided to see what the gender breakdown is for books that are recommended1 from the main subjects of the Slate article: Franzen, Hornby, Weiner and Picoult (who kicked off the debate with an angry comment about Franzen's rave in the Times, if I recall correctly).

The results are shocking. See below: boys in blue, girls in yellow (click on the thumbnails to see larger images).2 Yes, Franzen and Hornby are linked to a lot more men than women—not too surprising. Weiner is linked almost exclusively to women—again, not a huge surprise. But take a look at Picoult—she is a literary island unto herself, according to the Amazon recommendation engines. This is very rare in my research, and I think indicates an author who's distinctive in a stylistically interior way—her books lead readers to more of her books, not to things outside the Picoult universe.

I did this quickly so I might have gotten a gender wrong somewhere or messed up a book network somehow, but as a quick sketch of the differences between Franzen, Hornby, Weiner and Picoult, I think this is quite interesting. (Or at least the perceived differences, which in the literary world are more or less the whole of reality anyway). I don't have a strong opinion in the debate; it seems clear that more men than women are reviewed in the Times, while it's almost certainly true that many more women than men read novels. But as some comments on the Slate article pointed out, gender bias doesn't happen in a vacuum--readers, authors and critics are all players in the same complicated literary game.

1. I look at these recommendations because I think they're one of our best models for what books people actually buy together. In practice books connected this way tend to jump the boring categories like genre and author and link together in much more idiosyncratic ways. Obviously Amazon plays with these results...but they're always trying to sell more books, and they're pretty good at it, so I use the recommendations as a best approximation of the marketplace.

2. "What am I looking at?" The nodes here are books on Amazon, and the arrows connecting them are recommendations from one book page to another. These results represent the first ten “Customers who bought X also bought Y" recommendations for each book, starting with each writer's most recent fiction publication (Freedom, Juliet, Naked, Fly Away Home and House Rules, respectively).

Labels:

cultural comment,

writing

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)